An Idea Whose Time Has Come

The Aha! or Epiphany moment.

Most people believe that the best idea they had was borne of a moment in time. Yet, after the surge of adrenalin subsides and contemplation on the immensity of the idea begins, one realizes that transformative ideas do not appear from a vacuum. Rather, the idea emerged when one reflected upon a series of real events and incidents and then connected the dots. This is the soul of the entrepreneurial spirit; a journey that culminates into a precise moment, and says, as Einstein did, “If at first, the idea is not absurd, then there is no hope for it.”

So it is no surprise that 30 years ago I first observed someone asking an employer for a salary advance. The request was simple, “It is the 17th of the month. Can I get 10 days salary, and can you deduct it on the 1st when I get paid?” Fair enough, I thought. After all, this individual had already earned their money. Yet, the retort from the employer was anything but straightforward. “You better take control of your life and manage your finances better. I am not your bank and not a lender.” I was taken aback and today, all I can remember from that exchange was that someone in need had asked for money they had already earned, and they had been rebuffed.

Years later, while pursuing my graduate degree, I had my need-cash-NOW moment. I was earning $1100 per month, had savings of $235, and needed another $250 urgently. Coincidentally, this occurred on the 17th of the month and I had in theory already earned over $500. Yet, my money was stuck because payday was a couple of weeks away. Asking for a cash advance from my professor seemed a scary proposition so I decided to look within. The Safwan Shah plastic collection consisted of a Montgomery Wards store card and an American Express card, obtained through on campus credit card marketing campaigns. My first idea was to go to Wards, buy something, and resell it for cash. On a sub-zero, wintry day the idea was a nonstarter for many reasons, but more so when it occurred to me that anyone who gave me cash could just as easily walk into the store and buy the goods themselves.

A good nap had served me well in the past, and this time was no different. Upon awakening, I realized the answer had been in my wallet all along. The AmEx card was a multi-purpose Swiss knife, the delightful green goblin that could give me $250 instantaneously. I had discovered the magic of an instant cash advance. A quick phone call to AmEx, and soon I had instructions to find the right ATM. Just an hour later, I had the money. Problem solved! When I received my AmEx statement reflecting the balance plus 7% or so, due immediately, (because it was a charge card), I grumbled. Still, I paid the balance in its entirety with my next paycheck. Today, I remain grateful AmEx had the instant cash advance option, saving me from self-consciously standing in a bank branch or going to a pawnshop.

Fast-forward to 2002. I was now the CEO of Infonox, a payment technology company. We had built the technology platform that powered the risk, routing, and processing of financial transactions. One of our customers, Global Cash Access, was the largest operator of casino cash access services. Over 90% of the casinos in the world used their cash access services and our platform was involved in authorizing transaction approvals and cash dispensation.

For more exotic transactions requiring identity verification like cash advances, check cashing and money transfers, we provided the software necessary for ‘human’ cashiers to instantly obtain approvals and deliver cash to the patron. However, on casino floors, ATMs continued to be the go to mechanism through which basic cash access needs were served. One day the CEO of Global Cash Access, Kirk Sanford, asked me, “Can a vanilla ATM be converted into a virtual cashier?” He wanted a multi tasking ATM machine that would be able to: take a picture, verify the picture with an ID like a driver’s license, cash a check, receive a money transfer, issue a credit line, redeem rewards and pretty much do everything that a cashier did.

Equipped with our customer’s vision and funding, we took a vanilla ATM and loaded our software onto it (to the horror of NCR and Diebold), and a bank in a box called Automated Cashier Machine (ACM) was born. Soon there were hundreds of virtual cashiers retro-fitted with facial biometric cameras, ID scanners, fingerprint sensors, check imagers and scanners. The process of access-cash-now was born, and patrons used the ACM to cash checks, access cash, get a cash advance, or request a marker, all in seconds.

At the same time, we also knew millions in the U.S. were cashing payroll checks, transferring funds, paying bills and printing money orders in stores like 7-11 or Walmart. This was an opportunity to take the virtual cashier concept to the underbanked, and we did just that. We partnered with Western Union, which was still a part of the FDC at that time, and launched an even more advanced virtual cashier in HEB, Fry’s, Albertsons, and many other major grocery stores. The pilots were successful but not enough to get the funding needed for a major rollout.

Western Union decided to stay as a service provider but not the primary sponsor, and we were at an impasse. Unwilling to give up, we approached other institutions but failed to get the requisite funding. Everyone recognized that there were millions in the U.S. who needed alternative payment services but there wasn’t much willingness to make the necessary investment. Meanwhile, payday lenders rapidly filled the gap. They give cash advance against payroll, issued prepaid reloadable cards, and offered bill pay and other services. Users of payday advances services seemed so desperate that it didn’t matter that fees often exceeded the principal, and the process encouraged a horrific debt spiral.

Around that time, Infonox got acquired, and after a couple of years at a large corporation, I was on my own. My focus shifted to learning about the underserved. Internet payday lending was growing rapidly. Exotic short term lending applications using social graphs as risk mitigants were also gaining traction, as were social finance businesses where lenders and borrowers were algorithmically matched. I was struck by the fact that millions of consumers were collateralizing their future income for the very short term, high fee loans. The fees that people paid continued to trouble me, especially because these fees were only applicable to those that had the least income. In contrast, their wealthier counterparts, with savings and credit cards, readily used free bill pay and obtained low-interest credit cards, loans, and rewards. The contrast was counterintuitive and troubling.

Fees paid by lower-income families

- Bank accounts > $50 per year

- Bill Pay > $ 1 per bill

- Check Cashing > 1% face value

- Reloadable prepaid cards – a fee to load, a fee to access, a fee to talk to a person

- Money Transfer > $5 per transfer

- ATM cash > $2 each time

- Payday loans > $45 per $250 for 2 weeks

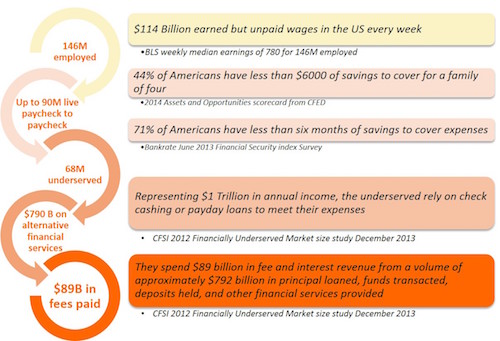

While I investigated this problem, the CFSI (Center for Financial Service Inclusion) began publishing stats on the staggering scale of the alternative financial services (AFS) industry – over 100 million lived paycheck-to-paycheck and over $89 billion paid in fees by the folks who were the poorest. Inspired, I undertook my own analysis. The following information stunned me –

Numerous questions overtook my thoughts:

- How could over $100 billion sit in the system every week, earned but not accessible?

- What if even 5% of these funds were made accessible to the employees who needed them the most? In 52 weeks, this amount would translate to $260 billion. What difference would that make?

- Would it help to eliminate predatory fees, overdraft risk, and predatory short term lending products?

- If we could overcome every technological obstacle to make it easier to spend money, why couldn’t we remove some of the obstacles that stood between the time income was earned and its access?

- Why were earnings digital and pre-designated when spending was analog and real-time?

Distressed, my preoccupation became finding answers to these questions. Ironically, I also started seeing the value that payday lenders were bringing to the consumer – timely access to cash. The problem was that these loans cost $45 per $250 borrowed, with a staggering 216% APR if the turnaround was one pay period. If you could not repay on the designated day and rolled over the advance, the APR would be much higher. Sequences of 10 rollovers were not uncommon. APR’s of 1600% were not unheard of. Lives spiraling into debt, despair, and devastation were all too common.

Today, despite these almost insurmountable costs, the payday lending industry continues to thrive for a basic reason – the industry meets a huge demand and fulfills an unmet need. Regulators, innovators, lenders, bankers, politicians, and philanthropists have all been caught off guard by the sheer scale and proportion of this industry. Shutting it down is not without peril. Where would the millions who need immediate access to cash for life’s emergencies turn?

This is where Payactiv steps in. Payactiv changes the status quo and gives consumers an alternative to short term lending products with security, dignity and savings. Waiting for payday is after all a consequence of the way payroll systems are structured. People who need immediate cash access are simply reacting to this system and their need does not presume judgment about their lifestyle. Our innovation is to systematically craft the partnerships and infrastructure that will bring earnings in alignment with spending. Instead of simply criticizing the existing short-term loan market, we offer a compelling alternative. The Payactiv proposition is to eliminate the possibility of debt. In fact, there is no lending or borrowing involved because we enable access to already earned money stuck in the system.

We take six major problems and provide a solution for each one of them

- Low approval rates – Everyone is approved (100%).

- Delay in getting cash access – Immediate.

- Separate fees for bills, remittance – No additional cost. One stop shop.

- Inadequate budgeting and savings for users – Cash management tools and cash back.

- Predatory Fees – Very low. Just like an ATM. No interest rate.

- Risk of debt spiral – Zero. None.

In the Payactiv model, people have access to earned money through the most vested and logical stakeholder in their financial lives – their employer. In turn, businesses can invest in their people by offering Payactiv’s products and benefit from increased productivity. We understand that a paycheck-to-paycheck person has no mechanism for income smoothing because this is a luxury enjoyed only by those with savings and credit cards. For the remaining 100 million people, there is Payactiv.

Get Payactiv for your business

Related Articles

Learn how Payactiv can help you take the friction out of pay advances with...

Compassionate workplace culture not only breeds happier employees, but also...

April is Financial Literacy Month, a great time for employers to focus on the...

© 2025 Payactiv, Inc. All Rights Reserved

24 hour support: 1 (877) 937-6966 | [email protected]

* The Payactiv Visa Prepaid Card and the Payactiv Visa Payroll Card are issued by Central Bank of Kansas City, Member FDIC, pursuant to a license from Visa U.S.A. Inc. Certain fees, terms, and conditions are associated with the approval, maintenance, and use of the Card. You should consult your Cardholder Agreement and the Fee Schedule at payactiv.com/card411. If you have questions regarding the Card or such fees, terms, and conditions, you can contact us toll-free at 1-877-747-5862, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

** Central Bank of Kansas City does not administer, nor is liable for earned wage access.

Payactiv holds earned wage access services (EWA) license number 2591928EWA with the Wisconsin Department of Financial Institutions.

Apple and the Apple logo are trademarks of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. App Store is a service mark of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries.

Google Play and the Google Play logo are trademarks of Google LLC.

Galaxy Store and the Galaxy Store logo are registered trademarks of Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd.